According to a report in the Sun Sentinel by Lisa J. Huriash relying on a police report, a “North Miami Beach police officer has been arrested, accused of refusing to take off a mask he wore while on the street protesting the federal government’s new healthcare law.” The protesting police officer interestingly adopted the Guy Fawkes mask (pictured below) made popular during Occupy protests, as a symbol.

According to the police report, the protesting police officer wouldn’t tell police who he was, “stating his anonymity was his cause, thus the mask. … He stated the mask was used by movement groups around the world for protest.” He was also carrying a gun, but was charged only with obstruction of traffic and “wearing a hood or mask on the street.”

The charge may be a difficult one to make stick. Florida’s anti-masking laws derive from attempts to criminalize KKK activities and are thus linked to intimidation and civil rights violations.

The Florida statute §876.21 definitely applies to the reported conduct:

Wearing mask, hood, or other device on public way.—No person or persons over 16 years of age shall, while wearing any mask, hood, or device whereby any portion of the face is so hidden, concealed, or covered as to conceal the identity of the wearer, enter upon, or be or appear upon any lane, walk, alley, street, road, highway, or other public way in this state.

BUT, another Florida statute, §876.155 limits the provisions the various anti-masking statutes, stating these statutes will apply only if the person was wearing the mask, hood, or other device:

(1) With the intent to deprive any person or class of persons of the equal protection of the laws or of equal privileges and immunities under the laws or for the purpose of preventing the constituted authorities of this state or any subdivision thereof from, or hindering them in, giving or securing to all persons within this state the equal protection of the laws;(2) With the intent, by force or threat of force, to injure, intimidate, or interfere with any person because of the person’s exercise of any right secured by federal, state, or local law or to intimidate such person or any other person or any class of persons from exercising any right secured by federal, state, or local law;(3) With the intent to intimidate, threaten, abuse, or harass any other person; or(4) While she or he was engaged in conduct that could reasonably lead to the institution of a civil or criminal proceeding against her or him, with the intent of avoiding identification in such a proceeding.

This is unlike statutory provisions in other states, such as New York, which prohibit “loitering while masked” or indeed the new Canadian criminal provision specifically aimed at protesting while masked.

The Florida statutory scheme could certainly be construed to include the protesting police officer’s acts under subsection (4) above, given that he stated he was trying to avoid identification (to protest anonymously) and that he was reportedly charged with another violation (obstructing traffic).

Where Is Your T-Shirt Made? And Who Makes It? Under What Conditions?

In her terrific new article for Mother Jones, Dana Liebelson discusses the links between India’s “sumangali” girls who work to save for their dowries and the clothes for sale in the West:

You won’t find a Western clothing manufacturer that openly approves of sumangali labor, but cracking down on it is a different matter. That’s because textile supply chains are vast and mind-numbingly complex. The average Indian T-shirt begins in a cotton field in western states like Gujarat and Maharashtra, where fluffy, plum-size balls are harvested by workers who generally come from the lower castes. From there, the balls are shipped in trucks to warehouses and sold to spinning mills, where machines (like the kind that cut Aruna’s hand) process raw cotton bales into thread. Then workers weave the thread into strips, dye them, and send them to factories that do final processing.

As Liebelson writes, it isn’t simply that the supply chains are “complex,” it’s also that manufacturers including retailers have great resistance to transparency. As I’ve suggested elsewhere, one possibility is to demand labeling on our clothes that would reveal not only its source but the conditions under which it is made – – – there could be a label “sweat free” analogous to the label “organic.” And there’s more on the relationship between work (including labor under chattel slavery) and the clothes we wear in the chapter “dressing economically.”

image via

image via

Continuing to Blame The Hoodie

George Zimmerman, charged (albeit belatedly) and notoriously found not guilty of the killing of Trayvon Martin, is in the news yet again, for another involvement with the law based on allegations of his violence.

George Zimmerman, charged (albeit belatedly) and notoriously found not guilty of the killing of Trayvon Martin, is in the news yet again, for another involvement with the law based on allegations of his violence.

For some, this (re)opens the issue of the trial for the death of the 15 year old Martin. This includes pundit Geraldo Rivera, who famously blamed Trayvon Martin’s “hoodie” and continues to do so. Rivera writes that although Zimmerman

may be nuts now, but was he nuts then? That’s the bigger issue, whether he is crazy because of the trauma of Trayvon’s death and his trial and being broke and besieged and aimless or was he crazy the night he killed the kid?

This seems within the realm of possibility. However, the validity Rivera’s obsession with Trayvon Martin’s hoodie as “thug wear” seems less plausible, arguing that even if Zimmerman did not act in self defense but was

a hunter looking for game that night, picking a fight because with his hand near that concealed weapon ready to draw and fire he knew he had the advantage, the verdict would have been closer.

Still, he would have been acquitted, because of the hoodie.

As I argue elsewhere, hoodies are ubiquitous items of clothing having no connection with the propensity to commit violence.

[image via]

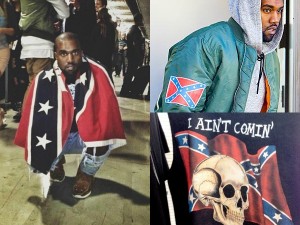

More About Confederate Flag Attire: Kanye West Edition

The controversy surrounding celebrity rapper Kanye West’s adoption of the Confederate flag for his new tour is expertly analyzed by Elon James White in his article in his article in The Root and there has been a call to boycott the tour gear.

But what if a student wanted to wear Kanye West attire to school, perhaps accepting West’s articulation about the symbol’s meaning?

Kanye West notwithstanding, the school can most likely constitutionally prohibit the student from wearing Confederate flag gear. Here’s my recent column for the London School of Economics blog, and we’ve previously covered the Confederate flag issue here and here.

[image via]

Dressing Like a Prostitute Does Not Include Skinny Jeans and a Pea Coat

New York Criminal Court Judge Felicia Mennin has dismissed a criminal complaint charging Loitering for the Purpose of Engaging in a Prostitution Offense (NY Penal Code § 240.37[2]) for facial insufficiency in her opinion in People of State of New York v. McGinnis  based in part on the failure of the officer’s description of the defendant’s attire to be meaningful.

based in part on the failure of the officer’s description of the defendant’s attire to be meaningful.

The criminal complaint alleged, that the officer observed “defendant wearing BLACK PEA COAT, SKINNY JEANS AND PLATFORM SHOES, which were revealing in that OUTLINE OF DEFENDANT’S LEGS [sic].”

Here’s Judge Mennin on the sufficiency of the officer’s statements:

The informant’s emphasis on the defendant’s clothing as a tell-tale sign that she was marketing herself commercially is astonishing. The defendant is alleged to have been wearing a black peacoat, skinny jeans which revealed the outline of her legs and platform shoes. This information was again supplied in the supporting deposition in response to a request to ”fill in the blank.“ Any current issue of a fashion magazine would display plenty of women similarly dressed. However, the choice of such outfit hardly demonstrates the wearer’s proclivity to engage in prostitution. Indeed, the complaint’s characterization of the jeans as ”revealing“ because they ”outlined the defendant’s legs“ seems more to be expected in the dress code of a 1950’s high school than a criminal court pleading.

That there is some type of dress that might be more probative of a willingness to engage in prostitution is also discussed by Judge Mennin, with reference to the cases cited by the State:

The defendant’s clothing in this case stands in stark contrast to the clothing relied upon as circumstantial proof of loitering for purposes of prostitution in the cases cited by the People. For instance, in Byrd, the defendant’s clothing exposed her buttocks. In Jones, the defendant was allegedly dressed in a skirt and a black bra with no other covering on her upper body. In Farra S., the defendant was wearing a shirt, the cut of which revealed the sides of her breasts. In Koss, one defendant was dressed in a black leopard two-piece bathing suit and high heels. In such instances, reliance upon attire as a factor appears more reasoned.

As a footnote to this passage, Judge Mennin addressed the implicit claim that a peacoat might be more provocative during the winter:

Granted, this incident occurred in the middle of winter. However, a ”pea coat“ is still standard issue to members of the U.S. Navy and models of such coats are made and sold routinely to men, women and children, and blue jeans, skin-tight or baggy, are practically an American icon. Accordingly, it is difficult to imagine what, if any, significance at all the defendant’s clothing might have in this case, either individually, or taken collectively with other meaningful circumstances, as any indicia of a link to prostitution. It would appear that the officer was just tempted to ”fill in“ this blank of the supporting deposition because it was there.

Judge Mennin’s opinion, which has generated some media coverage, highlights the perfunctory nature of most criminal complaints as well as the tenuous link between attire and sex work. While her opinion does not hold that attire can never be circumstantial evidence of loitering for the purpose of prostitution, she certainly concludes that the attire must approach indecent exposure.

Profiling Clothes: Stop and Frisk and What You’re Wearing

There is continuing controversy regarding law enforcement’s implementation of stop-and-frisk in racially discriminatory ways. Regarding NYC’s highly publicized practices, a federal district judge’s decision to enjoin the current practices was not only stayed by the Second Circuit, but the judge herself removed from the case, a removal which is being challenged. Meanwhile, with the election of a new mayor in New York City, the litigation may be moot.

There is continuing controversy regarding law enforcement’s implementation of stop-and-frisk in racially discriminatory ways. Regarding NYC’s highly publicized practices, a federal district judge’s decision to enjoin the current practices was not only stayed by the Second Circuit, but the judge herself removed from the case, a removal which is being challenged. Meanwhile, with the election of a new mayor in New York City, the litigation may be moot.

But whatever happens, there are certainly conversations about the possibilities of racially neutral criteria to support the “suspicion” constitutionally required by Terry v. Ohio under for stop and frisk. Many seemingly neutral criteria are in fact racial (and gendered) criteria. This includes clothes.

As I argue over at the Cambridge University Press blog 1584,

suspect attire mixes with race, gender, and age into a combustible cocktail targeting young men of color. The most explosive element is the racial one, for focusing on people based upon their race violates our basic understandings of constitutional equality. Current constitutional doctrine of equal protection, however, generally allows a racially disproportionate impact if there is no intent to be racially discriminatory. Enter clothes as convenient camouflage. Or, as one court phrased it, “although the prosecutor may have a bias ‘against people who sag,’” that does not mean the prosecutor’s exclusion of the juror was “based on race.”

Because, let’s be honest,

it is not every single person in a hoodie, in saggy pants, or in an university sweatshirt who merits suspect status. Indeed, the hooded sweatshirt has been around since the 1930s, was arguably popularized by the Rocky movies beginning in 1976 in which a boxer played by white actor Sylvester Stallone wears a hooded sweatshirt, and has been adopted and adapted by skaters, grunge artists, Facebook billionaires, and hip-hop culture. Saggy pants are often argued to have their source in the no-belt prison environment, but as white singer, model, and now actor “Marky” Mark Wahlberg demonstrated in the early 1990s with the Calvin Klein ads, fashionable underwear was meant to be seen, even while wearing pants. Today, it’s rare that underwear for men does not boast at least a waistband that is more than suitable for exposure. And as for clothes with university or pro-team logos, a visit to most colleges or to an NFL football game quickly demonstrates the popularity of these lucrative lines of apparel.

Let’s not allow attire to be a seemingly neutral rationale for masking other stereotypes. After all, as Dressing Constitutionally shows again and again, what we’re wearing is rarely, if ever, neutral.

[image via]

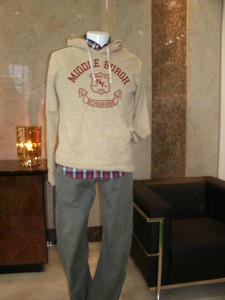

Supreme Court Asked to Fashion a Standard for Clothes

The United States Supreme Court today heard oral argument in Sandifer v. United States Steel Corporation centered on the meaning of “changing clothes” in section 203(o) of the Fair Labor Standards Act. As we discussed when the Court granted certiorari, the Seventh Circuit’s opinion by Judge Richard Posner found in favor of U.S. Steel that donning and doffing the safety gear was not necessarily changing clothes, because

not everything a person wears is clothing. We say that a person “wears” glasses, or a watch, or his heart on his sleeve, but this just shows that “wear” is a word of many meanings.

He included an image in the opinion (at right) and stated

Almost any English speaker would say that the model in our photo is wearing work clothes.

And indeed, Justice Ginsburg, during the oral argument at the Supreme Court did just that, but the discussion continued:

JUSTICE GINSBURG: But we’re dealing with here, from the picture, that looks like clothes to me.

MR. SCHNAPPER: Your Honor, I think that your question raises an excellent point. One of the problems with the picture is that it withholds from you other information that you would use to assess whether to describe it as clothes. You don’t know what -

JUSTICE KENNEDY: Except you would look and say, those clothes probably have something special underneath them. I mean, in ordinary parlance I think that would be a proper use of diction.

MR. SCHNAPPER: If you saw an airbag jacket, you would probably call it clothes unless you are an equestrian. It looks like a jacket. If you saw a compression torsion — a torso compression bandage in a photograph, you would call it clothes, because you don’t have all the relevant information.

JUSTICE ALITO: Why is it that the jacket and the pants in that picture are not clothes?

MR. SCHNAPPER: In our view — well, let me — part of it — first of all, they are designed for a protective function, to protect you from catching fire.

In addition to the ruminations on the meaning of clothes, perhaps leading to a definitional rule, there were attempts to understand why it mattered in this interpretation of the statute. The statute excludes from “hours worked”

any time spent in changing clothes or washing at the beginning or end of each workday which was excluded from measured working time during the week involved by the express terms of or by custom or practice under a bona fide collective-bargaining agreement applicable to the particular employee.

Thus an employee would need to be paid for putting on “gear.”

But if the Court can’t tell by simply looking, then what? As Justice Kagan noted toward the end of the argument, the distinction between clothes and gear “seems the quintessential question of statutory interpretation to which we would normally defer to the agency,” but in this case, the agency hasn’t issued a regulation. Justice Scalia offered his own explanation for the administrative failure to address the matter with a rule: “Too complicated is why.”

Thus, while Judge Posner’s opinion for the Seventh Circuit did raise some constitutional considerations about agency and executive power regarding differing meanings driven by politics, the constitutional question implicit in the Supreme Court arguments involve the separation of powers and the role of the Court in statutory interpretation.

So it is up to the Court to “fashion a standard,” as Eric Schnapper, representing Clifton Sandifer, phrased it during oral argument.

Halloween (II): Masks In Louisiana

Statutes criminalizing the wearing of masks often have a “Halloween exception.” But in some states – – – Louisiana, for example – – – the exception has an exception for a certain type of person.

Statutes criminalizing the wearing of masks often have a “Halloween exception.” But in some states – – – Louisiana, for example – – – the exception has an exception for a certain type of person.

Here’s the statute, §14.313:

A. No person shall use or wear in any public place of any character whatsoever, or in any open place in view thereof, a hood or mask, or anything in the nature of either, or any facial disguise of any kind or description, calculated to conceal or hide the identity of the person or to prevent his being readily recognized.

B. Whoever violates this Section shall be imprisoned for not less than six months nor more than three years.

C. Except as provided in Subsection E of this Section, this Section shall not apply:

(1) To activities of children on Halloween, to persons participating in any public parade or exhibition of an educational, religious, or historical character given by any school, church, or public governing authority, or to persons in any private residence, club, or lodge room.

(2) To persons participating in masquerade balls or entertainments, to persons participating in carnival parades or exhibitions during the period of Mardi Gras festivities, to persons participating in the parades or exhibitions of minstrel troupes, circuses, or other dramatic or amusement shows, or to promiscuous masking on Mardi Gras which are duly authorized by the governing authorities of the municipality in which they are held or by the sheriff of the parish if held outside of an incorporated municipality.

(3) To persons wearing head covering or veils pursuant to religious beliefs or customs.

D. All persons having charge or control of any of the festivities set forth in Paragraph B(2) of this Section, shall, in order to bring the persons participating therein within the exceptions contained in Paragraph B(2), make written application for and shall obtain in advance of the festivities from the mayor of the city, town, or village in which the festivities are to be held, or when the festivities are to be held outside of an incorporated city, town, or village, from the sheriff of the parish, a written permit to conduct the festivities. A general public proclamation by the mayor or sheriff authorizing the festivities shall be equivalent to an application and permit.

E. Every person convicted of or who pleads guilty to a sex offense specified in R.S. 24:932, is prohibited from using or wearing a hood, mask or disguise of any kind with the intent to hide, conceal or disguise his identity on or concerning Halloween, Mardi Gras, Easter, Christmas, or any other recognized holiday for which hoods, masks, or disguises are generally used.

Masks generally prohibited, except on Halloween (or Mardi Gras or other holidays) except for those who have to register as sex offenders.

More about masking as well as persons who must register as sex offenders because of public nudity or indecent exposure is in Dressing Constitutionally.

[image via]

Halloween (I): We’re a Culture Not a Costume

As Hallowee’en approaches, so too does the question of dress, or more specifically, costume.

The University of Colorado at Boulder has issued a statement – – – sensible and sensitive and recognizing First Amendment values. Here’s the statement from their website:

Halloween is a fun and celebratory occasion. It is often a time used to portray a character or symbol different than oneself. Unfortunately, stores often sell stereotypical and offensive costumes. If you are planning to celebrate Halloween by dressing up in a costume, consider the impact your costume decision may have on others in the CU community.

As a CU Buff, making the choice to dress up as someone from another culture, either with the intention of being humorous or without the intention of being disrespectful, can lead to inaccurate and hurtful portrayals of other peoples’ cultures in the CU community. For example, the CU-Boulder community has in the past witnessed and been impacted by people who dressed in costumes that included blackface or sombreros/serapes; people have also chosen costumes that portray particular cultural identities as overly sexualized, such as geishas, “squaws,” or stereotypical, such as cowboys and Indians. Additionally, some students have also hosted offensively-themed parties that reinforce negative representations of cultures as being associated with poverty (“ghetto” or “white trash/hillbilly”), or with crime or sex work.

The goal of CU-Boulder this Halloween and every day is to create a safe and welcoming environment for everyone.

CU-Boulder values freedom of expression and creativity both in and outside of the classroom. The CU community also values inclusiveness, respect and sensitivity. While everyone has the freedom to be expressive, we also encourage you to celebrate that you are a part of a vibrant, diverse CU community that strives toward respecting others.

Have a safe and fun Halloween.

However, some reporting on the issue as just another attempt at political correctness.

The “We’re a Culture Not a Costume” campaign seemingly started at Ohio University with a poster campaign that went viral.

Great reporting in 2011 on the issue from Colorlines and from The Root.

Unisex Hats in the United States Marines

The “integration” of women into the United States military (and military academies) has often raised the issue of clothes. The usual problems involve pants or skirts, pantyhose if skirts, make-up, and shoes.

But there are also hats.

Certain media outlets are headlining articles today “Obama wants Marines to Wear ‘Girly’ Hats.” For example, the NY Post proclaims,

Thanks to a plan by President Obama to create a “unisex” look for the Corps, officials are on the verge of swapping out the Marines’ iconic caps – known as “covers” — with a new version that some have derided as so “girly” that they would make the French blush.

Here’s a photo from the article in the Marine Corps Times contrasting the old hats with the proposed new hats and seeking input:

According to the NY Post, one set of hats for the “leathernecks” is more “shops of Christopher Street” than “Halls of Montezuma,” and might look “too French.”

In case you cannot tell which is which, the old (masculine) hats are on the left and the new (girly, French) hats are on the right.