cross-posted from Constitutional Law Professors blog December 20, 2012

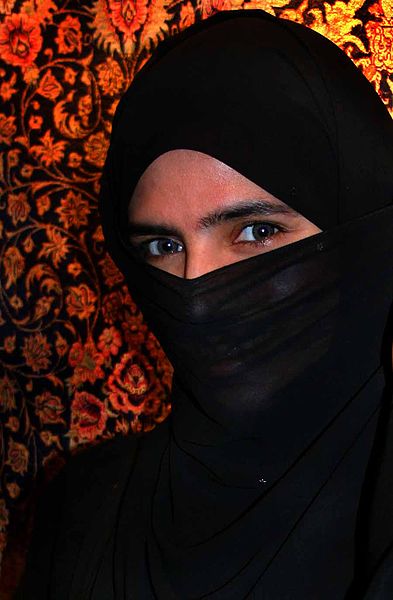

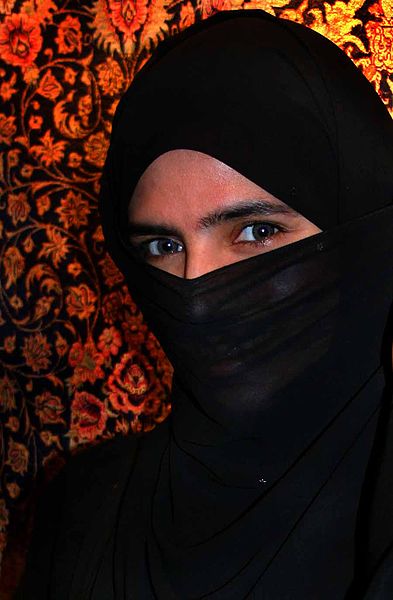

The Supreme Court of Canada finally issued its long-awaited opinion in December, in R. v. N.S., 2012 SCC 72, essentially affirming the provincial Court of Appeal of Ontario 2010 conclusion regarding the wearing of a niqab (veil) by a witness in a criminal proceeding and dismissing the appeal and remanding the matter to the trial judge.

The Supreme Court of Canada finally issued its long-awaited opinion in December, in R. v. N.S., 2012 SCC 72, essentially affirming the provincial Court of Appeal of Ontario 2010 conclusion regarding the wearing of a niqab (veil) by a witness in a criminal proceeding and dismissing the appeal and remanding the matter to the trial judge.

–>

In conflict were the religious rights of a witness in a trial in opposition to the rights of the accused to a fair trial, including the right to confrontation of witnesses. The accusing witness, N.S., is a Muslim woman who wished to testify at a preliminary hearing in a criminal case in which the defendants, N.S.’s uncle and cousin, were charged with sexual assault. The defendants sought to have N.S. remove her niqab when testifying. The judge heard testimony from N.S., in which she admitted that she had removed her niqab for a driver’s license photo by a woman photographer and she would remove her niqab if required at a security check. The judge then ordered N.S. to remove her niqab when testifying, concluding that her religious belief was “not that strong.” This determination of the “strength” of N.S.’s belief was one of the reasons for the remand as it troubled the Supreme Court.

The majority opinion, authored by Chief Justice Beverley McLachlin and joined by three of the Court’s seven Justices, began by noting the conflict of Charter rights at issue: the witness’s freedom of religion and the accused’s fair trial rights, including the right to make full answer and defence. The opinion quickly rejected any “extreme approach” that would value one right over the over, as “untenable.” Instead, the Court articulated the Canadian constitutional law standard of “just and proportionate balance” as:

A witness who for sincere religious reasons wishes to wear the niqab while testifying in a criminal proceeding will be required to remove it if (a) this is necessary to prevent a serious risk to the fairness of the trial, because reasonably available alternative measures will not prevent the risk; and (b) the salutary effects of requiring her to remove the niqab outweigh the deleterious effects of doing so.

In turn, this involved four separate inquiries:

First, would requiring the witness to remove the niqab while testifying interfere with her religious freedom as construed by section 2(a) of the Charter, which centers on a sincere (rather than “strong”) religious belief?

Second, would permitting the witness to wear the niqab while testifying create a serious risk to trial fairness? The opinion recognized the deeply rooted presumption that seeing a face is important, but noted that in litigation in which credibility or identification are not involved, failure to view the witness’ face may not impinge on trial fairness.

Third, assuming both rights are engaged, the trial judge must ask “is there a way to accommodate both rights and avoid the conflict between them?”

Finally, if accommodation is impossible, the judge should engage in a balancing test, asking whether

the salutary effects of requiring the witness to remove the niqab outweigh the deleterious effects of doing so? Deleterious effects include the harm done by limiting the witness’s sincerely held religious practice. The judge should consider the importance of the religious practice to the witness, the degree of state interference with that practice, and the actual situation in the courtroom – such as the people present and any measures to limit facial exposure. The judge should also consider broader societal harms, such as discouraging niqab-wearing women from reporting offences and participating in the justice system. These deleterious effects must be weighed against the salutary effects of requiring the witness to remove the niqab. Salutary effects include preventing harm to the fair trial interest of the accused and safeguarding the repute of the administration of justice. When assessing potential harm to the accused’s fair trial interest, the judge should consider whether the witness’s evidence is peripheral or central to the case, the extent to which effective cross-examination and credibility assessment of the witness are central to the case, and the nature of the proceedings. Where the liberty of the accused is at stake, the witness’s evidence central and her credibility vital, the possibility of a wrongful conviction must weigh heavily in the balance. The judge must assess all these factors and determine whether the salutary effects of requiring the witness to remove the niqab outweigh the deleterious effects of doing so.

In sending the case back to the trial judge (and instructing judges in similar situations in the future), the Court provides guidance, yet obviously falls far short of definitive answers.

The concurring opinion of two Justices argued that a “clear rule” should be chosen. This rule should be the removal of the niqab because a trial is a “dynamic chain of events” in which a conclusion about which evidence is essential can change.

Justice Rosalie Abella wrote the solitary dissenting opinion. On her view, while rooted in religious freedom, wearing a veil could certainly be analogized to other types of “impediments” in which the face or other aspects of demeanor might be obscured such as when a person is blind, deaf, not an English speaker, a child, or a stroke victim. Moreover, Abella argued:

Wearing a niqab presents only a partial obstacle to the assessment of demeanour. A witness wearing a niqab may still express herself through her eyes, body language, and gestures. Moreover, the niqab has no effect on the witness’ verbal testimony, including the tone and inflection of her voice, the cadence of her speech, or, most significantly, the substance of the answers she gives. Unlike out-of-court statements, defence counsel still has the opportunity to rigorously cross-examine N.S. on the witness stand.

Abella also stressed the specifics of the case involved: a sexual assault prosecution by a young woman in which the defendants were members of her own family.

The Canada Supreme Court’s opinion in R. v. N.S. is an important one seeking to balance rights and addressing an issue that is percolating in the United States courts.

The bill specifically allows the maintenance of gender specific dress and grooming codes by employers, but would allow some flexibility for individuals to choose their gender appearance:

The bill specifically allows the maintenance of gender specific dress and grooming codes by employers, but would allow some flexibility for individuals to choose their gender appearance: