In its opinion in Knight v. Thompson, the Eleventh Circuit upheld an Alabama Department of Corrections (DOC) policy that bans long hair for incarcerated men. A group of Native Americans initially challenged the policy in 1993, alleging it unlawfully burdens their religious tenet to wear unshorn hair. Over the last two decades, the case has worked its way to the Supreme Court with the group now petitioning the Court to hear their appeal.

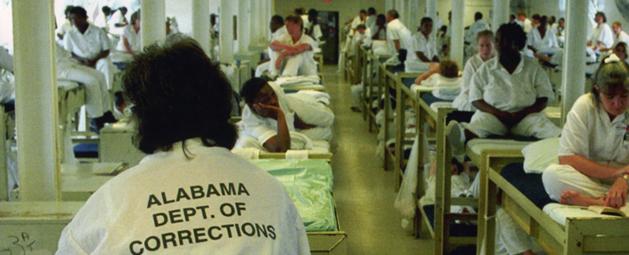

In total, Alabama prisons and jails house approximately 200 persons who practice the Native American faith of which having long hair is a fundamental belief. Despite numerous requests, the DOC has not given incarcerated Native Americans a religious exemption from the ‘no long hair’ policy. Thus, the group claims the policy is unlawful under Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act (RLUIPA).

RLUIPA allows a policy to infringe on incarcerated persons’ beliefs if the policy furthers a compelling interest and is the least restrictive means to achieve that interest. So, in defense of the policy, the DOC argues that safety concerns require the long hair ban — incarcerated persons could hide contraband in their hair or grab the hair during fights — and that long hair encourages gangs, undermines order and control, and raises hygiene issues. The challengers, however, argue that a total ban is not the least restrictive means to achieve safety and order — after all, Alabama’s women’s prisons allow long hair and over 38 men’s prisons in the U.S. do as well. But the lower court found that incarcerated women pose “less risk of violence and escape” than men based on warden testimony, and the circuit court also found that other prisons allowing long hair does not necessitate Alabama to do the same. Ultimately, the court denied the Native Americans’ claim, saying RLUIPA “does not give courts carte blanche to second-guess” prison officials.

The challengers also put forward a slew of Constitutional arguments — they claim the policy violates their 1st Amendments rights to free exercise of religion and freedom of association, and the right to due process and equal protection, among others. The court addressed only the equal protection claim, saying the remaining claims were not properly raised. And the court again upheld the policy, rejecting the equal protection challenge: given the finding that women pose less of a safety concern than men, it is not arbitrary or unreasonable to allow incarcerated women long hair but not men.

As discussed in Dressing Constitutionally, dubious rationales rooted in anecdotal evidence and broad generalizations are typically sufficient to justify a prison’s policy that treats groups differently. Indeed, despite lack of evidence or a challenger’s showing to the contrary, courts give a hefty deference to prison officials because of the weight given to safety concerns.

As discussed in Dressing Constitutionally, dubious rationales rooted in anecdotal evidence and broad generalizations are typically sufficient to justify a prison’s policy that treats groups differently. Indeed, despite lack of evidence or a challenger’s showing to the contrary, courts give a hefty deference to prison officials because of the weight given to safety concerns.

In response to the loss in the circuit, a member of the Native American petitioners told reporters, “I wish the courts could see or feel how something as simple as a lock of hair can mean.” Perhaps if confronted with the full meaning and the right (or lack thereof) at issue for an incarcerated person, the court might not be so quick to uphold a prison policy without a more rigorous showing of substantiated facts — adequately justifying why a prison finds it necessary to control a person’s physical appearance and thwart his personal, religious, or spiritual expression.