Can a student wear a pro-gun shirt to school? The preliminary issue is the school’s dress code and whether or not such a shirt would be a violation. This may not have a simple answer.

Can a student wear a pro-gun shirt to school? The preliminary issue is the school’s dress code and whether or not such a shirt would be a violation. This may not have a simple answer.

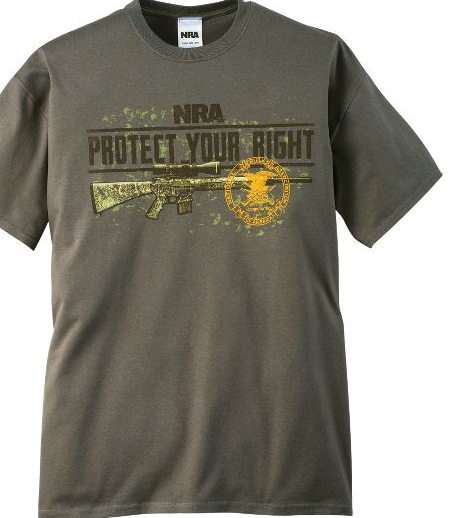

In the recent controversy surrounding Jared Marcum, an eighth grader in Logan, West Virginia, was reportedly suspended and arrested for wearing a t-shirt portraying an assault rifle with the slogan “NRA Protect Your Right.” More recently an attorney for Logan County Schools reportedly said that “the T-shirt did not violate the school’s rules,” and that “Marcum was not suspended for his t-shirt, but confidentially prohibited him from saying anything more.”

And in another situation, in Connecticut, 18-year-old high school student Matt Zingarella wore a shirt portraying an assault weapon with the slogan “I Plead the 2nd.” As reported, he also argued that he had “read the handbook, there was nothing against it.”

Both students, like most people, quickly articulated a First Amendment rationale for their dress. Marcum reportedly initially explained to police that he would not sit down and be quiet, stating “No, I’m exercising my right to free speech” and has since become a media advocate, saying “What they’re doing is trying to take away my rights, my freedom of speech and my second amendment.” Similarly, Zingarella argued he was “expressing [his] beliefs through the shirt.”

The watershed case of Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District involved the wearing of black armbands by school students in protest of the Vietnam War. Decided by the United States Supreme Court in 1969, Tinker established the substantial and material disruption standard for evaluating school speech. While the Court actually uses the word “interfere” more often than “disrupt,” and uses the terms synonymously, what has become known as the Tinker disruption standard requires that in order to curtail student speech, school authorities must show that the student speech would materially and substantially interfere with appropriate school discipline. In Tinker itself, the Court noted that “the record does not demonstrate any facts which might reasonably have led school authorities to forecast substantial disruption of or material interference with school activities” because a few students wore black armbands.

Yet the Court in Tinker also noted that the black armbands did not implicate the “rights of other students to be secure and to be let alone,” thus suggesting this should be a factor. Additionally, Tinker found it “relevant” that the school did not prohibit the wearing of all symbols of political or controversial significance, and had allowed the wearing of “buttons relating to national political campaigns,” and even “the Iron Cross, traditionally a symbol of Nazism,” thus raising the specter of viewpoint discrimination.

Thus, the “substantial disruption” standard is only part of the relevant doctrine. The “rights of others” consideration should also factor into any decision. In cases about Confederate flag t-shirts and other clothing, courts have looked at incidents of racial violence in the schools. In the case of gun-rights t-shirts, the question of previous gun violence in the school and perhaps in the community, might also be relevant. Wearing a pro-gun t-shirt in Connecticut – – – home of the December Newtown massacre of 20 first graders and 6 teachers in a school – – – should be viewed as infringing on the rights of others who might have been personally affected and may still be reeling from the violence.

Further, what the school dress code actually provides is exceedingly relevant for First Amendment purposes. Perhaps ironically, a code that prohibited all political messages or all images on t-shirts or all images of guns, violence, and drugs, would probably be most likely to survive a First Amendment challenge.

As for Jared Marcum, he has presented a straightforward narrative that he was immediately disciplined merely for wearing a pro-NRA shirt. The school board attorney suggested that it may not be so simple. What if Jared himself has a history of violence at the school? Or what if Jared made threats involving firearms? After the Columbine High School massacre in 1999, schools began looking more closely at students’ violent propensities despite students’ First Amendment rights. The threat of a very substantial disruption – – – another school shooting – – – is one that the school officials are not going to take lightly.

[image via]