The United States Supreme Court today heard oral argument in Sandifer v. United States Steel Corporation centered on the meaning of “changing clothes” in section 203(o) of the Fair Labor Standards Act. As we discussed when the Court granted certiorari, the Seventh Circuit’s opinion by Judge Richard Posner found in favor of U.S. Steel that donning and doffing the safety gear was not necessarily changing clothes, because

not everything a person wears is clothing. We say that a person “wears” glasses, or a watch, or his heart on his sleeve, but this just shows that “wear” is a word of many meanings.

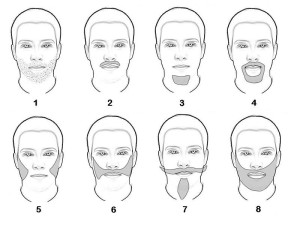

He included an image in the opinion (at right) and stated

Almost any English speaker would say that the model in our photo is wearing work clothes.

And indeed, Justice Ginsburg, during the oral argument at the Supreme Court did just that, but the discussion continued:

JUSTICE GINSBURG: But we’re dealing with here, from the picture, that looks like clothes to me.

MR. SCHNAPPER: Your Honor, I think that your question raises an excellent point. One of the problems with the picture is that it withholds from you other information that you would use to assess whether to describe it as clothes. You don’t know what -

JUSTICE KENNEDY: Except you would look and say, those clothes probably have something special underneath them. I mean, in ordinary parlance I think that would be a proper use of diction.

MR. SCHNAPPER: If you saw an airbag jacket, you would probably call it clothes unless you are an equestrian. It looks like a jacket. If you saw a compression torsion — a torso compression bandage in a photograph, you would call it clothes, because you don’t have all the relevant information.

JUSTICE ALITO: Why is it that the jacket and the pants in that picture are not clothes?

MR. SCHNAPPER: In our view — well, let me — part of it — first of all, they are designed for a protective function, to protect you from catching fire.

In addition to the ruminations on the meaning of clothes, perhaps leading to a definitional rule, there were attempts to understand why it mattered in this interpretation of the statute. The statute excludes from “hours worked”

any time spent in changing clothes or washing at the beginning or end of each workday which was excluded from measured working time during the week involved by the express terms of or by custom or practice under a bona fide collective-bargaining agreement applicable to the particular employee.

Thus an employee would need to be paid for putting on “gear.”

But if the Court can’t tell by simply looking, then what? As Justice Kagan noted toward the end of the argument, the distinction between clothes and gear “seems the quintessential question of statutory interpretation to which we would normally defer to the agency,” but in this case, the agency hasn’t issued a regulation. Justice Scalia offered his own explanation for the administrative failure to address the matter with a rule: “Too complicated is why.”

Thus, while Judge Posner’s opinion for the Seventh Circuit did raise some constitutional considerations about agency and executive power regarding differing meanings driven by politics, the constitutional question implicit in the Supreme Court arguments involve the separation of powers and the role of the Court in statutory interpretation.

So it is up to the Court to “fashion a standard,” as Eric Schnapper, representing Clifton Sandifer, phrased it during oral argument.