The intertwining of our clothes and our Constitution raise fundamental questions of hierarchy, sexuality, and democracy. From our hairstyles to our shoes, constitutional considerations both constrain and confirm our daily choices. In turn, our attire and appearance provide multilayered perspectives on the United States Constitution and its interpretations. Our garments often raise First Amendment issues of expression or religion, but they also prompt questions of equality on the basis of gender, race, and sexuality. At work, in court, in schools, in prisons, and on the streets, our clothes and grooming provoke constitutional controversies. Additionally, the production, trade, and consumption of apparel implicate constitutional concerns including colonial sumptuary laws, slavery, wage and hour laws, and current notions of free trade. The regulation of what we wear – or don’t – is ubiquitous. From a noted constitutional scholar and commentator, this book examines the rights to expression and equality, as well as the restraints on government power, as they both limit and allow control of our most personal choices of attire and grooming.

See the Table of Contents and Read the Introduction here

US BOOK LAUNCH/PRESENTATION at CUNY LAW September 19, 2013

CANADA Book Launch/Presentation at Osgoode Hall September 23, 2013

UK Book Launch/Presentation: November 26, 2013Listen to a 5 minute interview with Jacki Lyden aired on NPR’s ALL THINGS CONSIDERED here; a 12 minute interview with Mocrieff aired on NewsTalk IRISH radio here (starts at 35:00); a 60 minute interview on NPR’s The Diane Rehm Show here; a 20 minute interview with Brian Lehrer of WNYC here; a 15 minute interview on LA’s KPCC “AirTalk” with Larry Mantle on school dress codes here; a 60 minute discussion on Wisconsin Public Radio’s The Joy Cardin Show here; a 15 minute discussion with Margaret Ramirez on CUNY’s “Book Beat” here.

Read an interview with Carrie Murphy on the fashion site Refinery29 here; an interview on UK’s LawBore here; a BBC article on the book here; a review by Dean and Professor Kim Brooks in Jotwell here.

BUY THE BOOK

at your local independent bookstore,

direct from Cambridge University Press (PB US $32.99),

or as an e-book (Kindle app) (US less than $15)

Clothing Labels: Certifying Sweat-Free

What should a clothing label tell us?

In a piece in the LA Times, I argue that mandating labels that tell us whether or not a piece of apparel is – – – or is not – – – sweat-free or manufactured in safe conditions is an idea whose time has come, despite the First Amendment problems.

[image via]

From the UK: Virgin Trains Dress Code

The UK Guardian has the full story ((h/t Sonia Lawrence), discussing

reports that Virgin Trains’ female staff have rejected their new uniform as it includes a “flimsy” and “revealing” red blouse that they believe would allow passengers to see any dark coloured underwear.

It also reports on the “solution”:

The firm’s business support director, Andy Cross, has reportedly responded to the concerns, writing on the Virgin staff website: “It’s important that our people feel comfortable and so we will be issuing vouchers in the next few days for ladies to buy undergarments to wear under their blouses.” Apparently the vouchers are to the value of £20 and the implementation of the new uniforms has been put back.

As the story says, employment dress codes are nothing new.

Chapter 4 of Dressing Constitutionally is entitled “Dressing Professionally.”

Court Decides: Bikini v. Pastie

District Judge Fred Biery, known for his lively and pun-filled writing as in last year’s First Amendment Establishment Clause opinion on school prayer, has issued a suggestive order denying a preliminary injunction in “The Case of the Itsy Bitsy Teeny Weeny Bikini Top v. The (More) Itsy Bitsy Teeny Weeny Pastie.” (The actual name of the case is 35 Bar and Grille, LLC v. City of San Antonio).

In this First Amendment challenge, plaintiffs are businesses employing “exotic dancers” who claim that a 2012 amendment to the San Antonio Code of Ordinances (see Chapter 21, Article IX, Sexually Oriented Businesses) would require them either to submit to licensure or require their dancers to switch from pasties to bikini tops. The businesses claim infringement of the dancers’ free expression and that San Antonio has not satisfied its burden under the secondary effects doctrine to demonstrate harm.

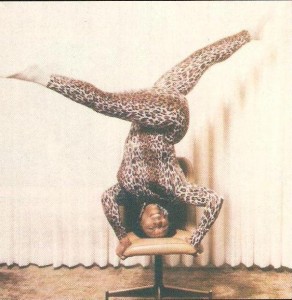

Noting that customers might better enjoy a performance by the fully-clothed Miss Wiggles (pictured), Judge Biery encourages the parties to engage in “reasonable discovery intercourse as they navigate the peaks and valleys of litigation, perhaps to reach a happy ending.”

While Biery’s opinion does illustrate the tendency of many courts to trivialize First Amendment claims regarding nudity, his previous opinions are evidence that his light treatment of partially clothed expression is not unique.

[image via]

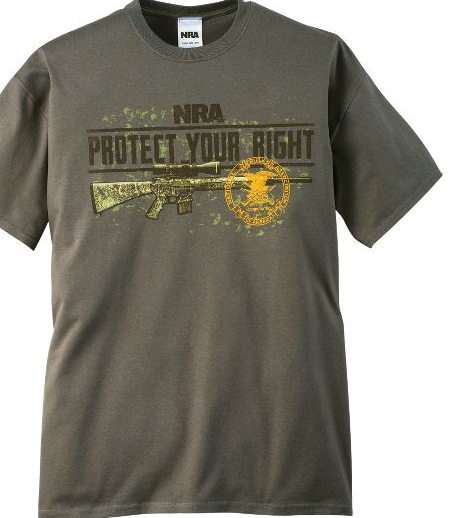

Students Wearing Pro-Gun Shirts to School: The First Amendment Implications

Can a student wear a pro-gun shirt to school? The preliminary issue is the school’s dress code and whether or not such a shirt would be a violation. This may not have a simple answer.

Can a student wear a pro-gun shirt to school? The preliminary issue is the school’s dress code and whether or not such a shirt would be a violation. This may not have a simple answer.

In the recent controversy surrounding Jared Marcum, an eighth grader in Logan, West Virginia, was reportedly suspended and arrested for wearing a t-shirt portraying an assault rifle with the slogan “NRA Protect Your Right.” More recently an attorney for Logan County Schools reportedly said that “the T-shirt did not violate the school’s rules,” and that “Marcum was not suspended for his t-shirt, but confidentially prohibited him from saying anything more.”

And in another situation, in Connecticut, 18-year-old high school student Matt Zingarella wore a shirt portraying an assault weapon with the slogan “I Plead the 2nd.” As reported, he also argued that he had “read the handbook, there was nothing against it.”

Both students, like most people, quickly articulated a First Amendment rationale for their dress. Marcum reportedly initially explained to police that he would not sit down and be quiet, stating “No, I’m exercising my right to free speech” and has since become a media advocate, saying “What they’re doing is trying to take away my rights, my freedom of speech and my second amendment.” Similarly, Zingarella argued he was “expressing [his] beliefs through the shirt.”

The watershed case of Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District involved the wearing of black armbands by school students in protest of the Vietnam War. Decided by the United States Supreme Court in 1969, Tinker established the substantial and material disruption standard for evaluating school speech. While the Court actually uses the word “interfere” more often than “disrupt,” and uses the terms synonymously, what has become known as the Tinker disruption standard requires that in order to curtail student speech, school authorities must show that the student speech would materially and substantially interfere with appropriate school discipline. In Tinker itself, the Court noted that “the record does not demonstrate any facts which might reasonably have led school authorities to forecast substantial disruption of or material interference with school activities” because a few students wore black armbands.

Yet the Court in Tinker also noted that the black armbands did not implicate the “rights of other students to be secure and to be let alone,” thus suggesting this should be a factor. Additionally, Tinker found it “relevant” that the school did not prohibit the wearing of all symbols of political or controversial significance, and had allowed the wearing of “buttons relating to national political campaigns,” and even “the Iron Cross, traditionally a symbol of Nazism,” thus raising the specter of viewpoint discrimination.

Thus, the “substantial disruption” standard is only part of the relevant doctrine. The “rights of others” consideration should also factor into any decision. In cases about Confederate flag t-shirts and other clothing, courts have looked at incidents of racial violence in the schools. In the case of gun-rights t-shirts, the question of previous gun violence in the school and perhaps in the community, might also be relevant. Wearing a pro-gun t-shirt in Connecticut – – – home of the December Newtown massacre of 20 first graders and 6 teachers in a school – – – should be viewed as infringing on the rights of others who might have been personally affected and may still be reeling from the violence.

Further, what the school dress code actually provides is exceedingly relevant for First Amendment purposes. Perhaps ironically, a code that prohibited all political messages or all images on t-shirts or all images of guns, violence, and drugs, would probably be most likely to survive a First Amendment challenge.

As for Jared Marcum, he has presented a straightforward narrative that he was immediately disciplined merely for wearing a pro-NRA shirt. The school board attorney suggested that it may not be so simple. What if Jared himself has a history of violence at the school? Or what if Jared made threats involving firearms? After the Columbine High School massacre in 1999, schools began looking more closely at students’ violent propensities despite students’ First Amendment rights. The threat of a very substantial disruption – – – another school shooting – – – is one that the school officials are not going to take lightly.

[image via]

No Seersucker Suits in Missouri

Missouri State Senator Ryan McKenna proposed that seersucker suits be prohibited garb for anyone over the age of 8. His amendment was to SB437 seeking to modify the way the state funds public institutions of higher education by creating a new model for calculating institutions’ state funding.

Reportedly, while the senator’s amendment was in “jest,” it was a response to a trend among Missouri legislators wearing seersucker suits.

The United States Congress has its own tradition of “Seersucker Thursday,” adopting the Southern style lightweight-weight fabric as summer begins in June.

[image: Seersucker Thursday in Senate,2006, via]

“She ought to be in prison for wearing a hijab”

Here is commentator Ann Coulter on the First Amendment free exercise rights of an American citizen:

http://youtu.be/o-XVEwNqnh0?t=2m38s

Coulter’s prescriptive statement is obviously not descriptive of First Amendment doctrine.

Second Amendment School “Uniforms”

What’s new in school clothes suitable for a robust Second Amendment?

According to TechBlog, it’s bullet proof uniforms, already in the testing phase:

http://youtu.be/8M4_4-XpfuQ

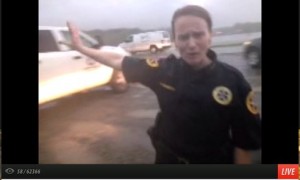

Off-duty Officers Don Uniforms for Exxon

Authorized by their departments, police officers are wearing their official uniforms while moonlighting for Exxon in response to a recent oil spill. Exxon’s Pegasus pipeline runs from Illinois to Texas, carrying more than 90,000 barrels of crude oil per day. On Friday, March 29, a leak in the pipeline flooded Mayflower, Arkansas, with thousands of gallons of oil, requiring the evacuation of 22 homes and wreaking havoc on the environment.

to Texas, carrying more than 90,000 barrels of crude oil per day. On Friday, March 29, a leak in the pipeline flooded Mayflower, Arkansas, with thousands of gallons of oil, requiring the evacuation of 22 homes and wreaking havoc on the environment.

The oil giant’s response has prompted various ridicule, including Rachel Maddow’s jabs for its use of paper towels in the cleanup and Stephen Colbert’s satirical mockery of the fairly effective efforts to create “press blackout” (see for example, threats of arrests made to reporters).

Additionally, the cleanup effort raises a novel issue — as reported, Exxon now employs “at least 19 local law enforcement officers in uniform as security guards” during their off duty hours.

One official was reported saying that Exxon requires the off-duty officers to wear their police uniforms, while an Exxon spokesperson told reporters that “whether an officer wears the uniform is up to the individual.”

The Arkansas Sheriffs’ Association told reporters that if the officers’ department approves then “officers are allowed to wear their uniforms, even when off duty and working for a private company.”

The Arkansas Sheriffs’ Association told reporters that if the officers’ department approves then “officers are allowed to wear their uniforms, even when off duty and working for a private company.”

Some argue, including local County Judge Allen Dodson who is helping to oversee the efforts, that police officers are performing similar services for Exxon as when on duty — providing protection and helping the community. Others, however, are concerned about potential conflicts of interest (including those threats of arrests made to reporters).

While officers may not have a First Amendment right to wear their uniforms when prohibited by the department, wearing a uniform imbued with state authority in service of a private company complicates matters, including raising questions of state action in light of any foreseeable constitutional claims.

First Class Jeans

Are jeans appropriate attire for a first class cabin on an airline? According to a complaint filed in federal court in California in Warren v. U.S. Airways, some airline employees think the answer depends upon the race of the body wearing the jeans.

According to the complaints’ allegations, two African-American men boarding a plane in Denver on a flight to L.A. were told that they needed to change their clothes in order to use their first class tickets because “everyone in first class is required to wear slacks, button up shirts, and no baseball caps.” The men, brothers, changed their clothes and boarded the plane. Other men in first class, however, did not conform to the announced dress code. Indeed, according to the allegations, a pair of men – – – one white and one Filipino – – – were both wearing jeans and hooded sweatshirts. These men stated that they were never informed there was a dress code for first class cabin.

According to the complaints’ allegations, two African-American men boarding a plane in Denver on a flight to L.A. were told that they needed to change their clothes in order to use their first class tickets because “everyone in first class is required to wear slacks, button up shirts, and no baseball caps.” The men, brothers, changed their clothes and boarded the plane. Other men in first class, however, did not conform to the announced dress code. Indeed, according to the allegations, a pair of men – – – one white and one Filipino – – – were both wearing jeans and hooded sweatshirts. These men stated that they were never informed there was a dress code for first class cabin.

The airline, as a private rather than governmental entity, is not subject to constitutional constraints. However, the airline is subject to several federal statutes that prohibit discrimination on the basis of race, including in public accommodations, by recipients of federal funding, and in the impairment of contracts. The complaint also includes a state law discrimination claim as well as state law tort claims for infliction of emotional distress.

If the plaintiffs can prove their allegations, the airline has cause to worry that its employees have engaged in racial discrimination. And if the plaintiffs can get to a jury, it would be unlikely anyone on that jury who has been a customer of an airline in the past several year will find a first class cabin “dress code” credible.

[image via]